As the last submissions for the Art of War contest come rolling in, we speak to Professor Joanna Bourke, a celebrated historian and the award-winning author of our prize giveaway book, War and Art.

Of course, if you're not one of the lucky winners, or if you're simply not entering the competition, you can still get your hands on a copy of this fascinating and beautifully illustrated book here, direct from the publisher, Reaktion Books. Joanna's Bourke's next work is coming out in October, later this year and will also be available from the publisher, as well as all good bookshops.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

I am an historian, based at Birkbeck (University of London), who has spent much of my career exploring the dark side of human experiences. Although I have published 13 books, the one readers seem to enjoy the most is An Intimate History of Killing, which came out in 1999 and won both the Wolfson Prize and the Fraenkel Prize. Other books explore topics such as dismemberment, rape, fear, pain, what it means to be human, and militarism.

I am an historian, based at Birkbeck (University of London), who has spent much of my career exploring the dark side of human experiences. Although I have published 13 books, the one readers seem to enjoy the most is An Intimate History of Killing, which came out in 1999 and won both the Wolfson Prize and the Fraenkel Prize. Other books explore topics such as dismemberment, rape, fear, pain, what it means to be human, and militarism.

In other words, I write about very grim topics. Why are “good people” sometimes so cruel? How can we explain why peaceful men and women can be easily trained to kill other people in times of war? Sexual violence will affect 1 in every 5 girls and women; why? How have people strived to find meaning in violence? I set out to explore the cultural, political, and military factors that make imagining, designing, playing with, and using weapons so enticing. What is the relationship between everyday violence (both imaginary and real) and war? How can we forge more peaceful worlds?

And what inspired your book, 'War and Art'?

I love modern art – so fusing my intellectual obsession with violence with my personal passion for aesthetics seemed natural! Artists have always made significant contributions to war. Everything from excitable patriotism to down-to-earth curiosity has led millions of artists into the heart of darkness that is war. They have represented armed conflicts in oil and water paints, pencils and crayons, silk and wool, carved wood, photographic film, digital technologies, and blood. They have sketched in the trenches, tattooed bullet casings, and painted garish images on the fuselage of fighter planes. Governments have employed artists to bolster morale and tell lies about the incredible cruelty of battle. Conscious of the power of representation, governments routinely seek to control the framing of visual messages. They seduce them with lucrative contracts and, if that fails, censor their work. In more recent decades, they embed artists in military units where artists inevitably view the conflict through the eyes of their “brothers in arms”. Other artists have used their talents to create searing indictments of the inhumanity of war. Such artists portrayed both the bitterness and the vulnerability of modern war. They attempted to visually represent the sound of grenades detonating, the stench of high explosives, the metallic taste of blood, and the sight of human bone, muscle, tissue, skin, hair, and fat strewn around. It was a tradition of anti-war art rejected by more recent artists (I am thinking of images such as Alfredo Jaar’s “Real Pictures”) which turn to the inarticulate sorrows of trauma and memory.

(Image): Alfredo Jaar's Real Pictures; a contemporary installation inspired by the artist's journey to a war-ravaged Rwanda. The work consists of many stacked, black linen portfolio boxes, containing a photograph. Texts on the boxes describe the hidden images inside, creating a sense of absence and compelling viewers to imagine what are, for many, the invisible realities of war. Source: Real Pictures (1995). Alfredo Jaar. Source: https://en.csw.torun.pl

Why is the subject of war important for art and artists?

War is important for artists for many of the same reasons that it is important for all of us: militarist values and practices destroy lives. Our loved ones are maimed and killed in military encounters. People we care about slaughter those strangers we might have learnt from, laughed with, and loved. War is terrifying; enticing; formidably destructive; aesthetically awesome. It permeates our language, invades our dream-space, and entertains us at the movies or in front of game-consoles. It is what makes us both human and inhuman.

What do you think makes a good war artist?

Passion and engagement, not only aesthetically but intellectually.

Is all war art propaganda?

It depends what you mean by “propaganda." Defining “propaganda” in the narrowest sense – that is, art that is commissioned by the state or other official authority – only accounts for a tiny proportion of war art. However, a great deal of war art is propaganda in the weaker sense that it propagates a deliberately distorted image of battle and other wartime experiences. Many artists are anxious to avoid demeaning servicemen or denying their “sacrifices” – heroic motifs might therefore be seen as more respectful than portraying murderous aggression. What is the harm of a few “white lies” to comfort grieving families and friends? Patriotism also demands it. There is an even more diluted meaning of “propaganda” – does war art necessarily “propagate” an ideological view. To this, the answer must be “yes”. All art conveys messages to audiences. The best art transfixes viewers, so we can barely turn away.

(Image): Many celebrated works of war art compound false ideas of conflict and can be labeled propagandistic. Although technically accomplished, Richard Caton Woodville's Grenfell VC arguably provides a myopic and unfaithful vision of the First World War at a time when many felt more accurate creative perspectives were needed. Source: Grenfell VC (1914). Richard Caton Woodville. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

What can depictions of war in art achieve?

Depictions of war in art can change the world – literally. By conveying something of the “truth” of combat, war art can encourage empathetic responses towards its victims. However, there is no guarantee that even self-consciously anti-war art will encourage pacifistic responses, let alone promote a politics that abhors violence. Art has been used to glamorise wounding and killing. This is a dilemma that many artists have addressed.

Can we consider video games works of art?

One of the things I set out to do in my book War and Art was to break down what used to be (and, for some, still is) the distinction between “high” and “low” art. This is why there are chapters on video art, children’s art, trench art, war films, and murals. Video games are extraordinary forms of artistic expression. I have written about war-gaming in another book I wrote, entitled Wounding the World (published by Virago). I was particularly interested in the commitment to detail in these modern games (it could almost be called fetishization of “the real”).

And what about photography? Can we call that 'art'?

War photography is one of my favourite artistic genres. Take the work of photographer Melanie Friend. She addresses the difficulty of creating art out of trauma without moralising or lingering over the (fetishized) bodies of mutilated and dead children, women, and men. In her series “Homes and Gardens: Documenting the Invisible,” Friend photographed the exterior and interior of homes of Albanian Kosovars who had been beaten, tortured, and otherwise treated cruelly by the Serbian police and security forces in the mid-1990s. These calm, orderly spaces, devoid of people and any signs of violence, were then juxtaposed with voiced testimonies in which the inhabitants spoke of their persecution. Viewing her photographs, audiences cannot help but be struck by absences and echoes of trauma in those bare rooms. The invisibility of the violence sheds new light on what had taken place.

Do you have a favorite war artist or work of art?

Well, clearly I love Melanie Friend! But if I had to choose someone else, it would be Peter Howson, the Scottish artist who, at the age of 35, was chosen by the Imperial War Museum and The Times newspaper to serve as the official war artist in Bosnia. He was embedded in the British Army contingent attached to the UN Peacekeeping Force. If I were to choose one painting, it would be Howson’s depiction of wartime rape in “Croatian and Muslim” (1994). Nothing could be further from heroic motif of wartime art than this scene of sexual assault. Two men press a woman’s head into a toilet while one brutally rapes her. It is a domestic scene, as one of the attackers steadies himself against a family portrait. In the doorway, someone watches. The painting is a repudiation of that distinction between home-front rhetoric and combat aesthetics: the raped woman is at home; it is war at its most brutal in the heart of Europe.

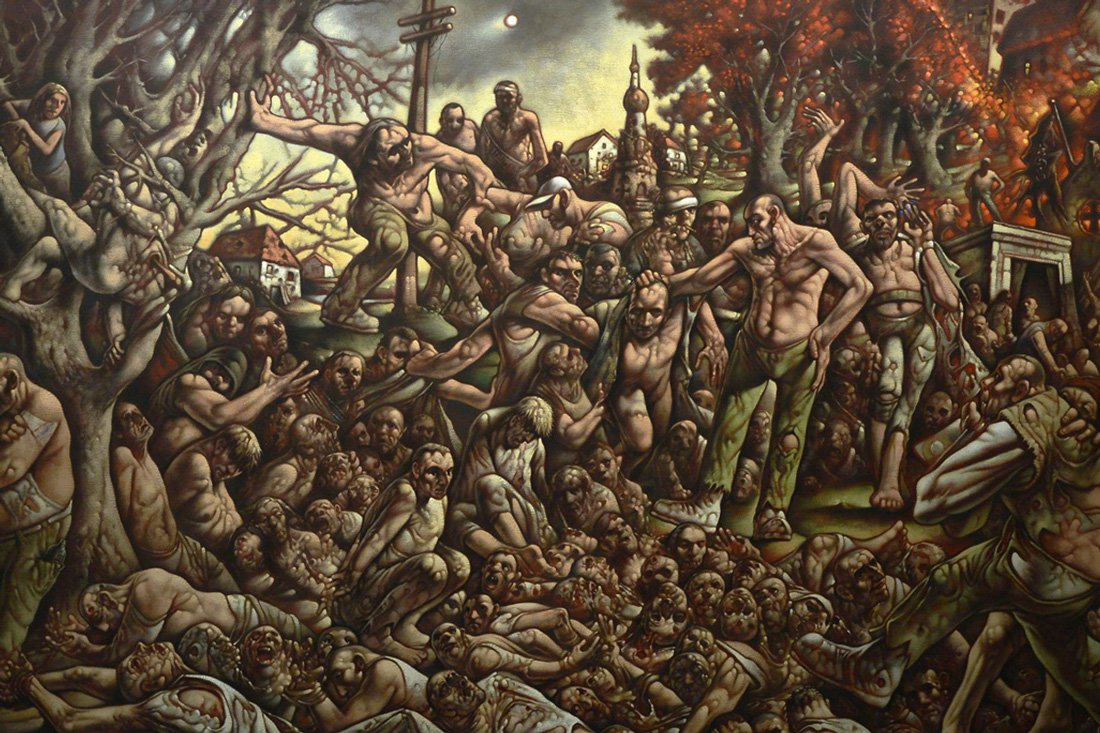

(Image): The Massacre of Srebrenica (2019) by the Scottish painter, Peter Howson, depicts a tragic act of genocide that shocked the world during the Bosnian Civil War. In this particular episode, more than 8,000 Bosniaks lost their lives. Howson was asked to cover the conflict as Britain's official war artist. Source: The Massacre of Srebrenica (2019). Peter Howson. Source: peterhowson.co.uk

What responsibilities do you feel video game developers have in terms of art and war?

Video game developers have a duty to create.

What do you think the future holds for war and art?

Art that has emerged through reflections on armed conflicts have always been powerful aesthetically, in part because the extreme violence of war exposes contradictions in what it means to be human. Although communion and affection are what everyone seeks, war presents us with exactly the opposite. After all, what is unique about war is not dying (which happens to us all) but killing (which is rare in non-war contexts). This means that artists have to think very hard about the ethics of representing violence. Perhaps the most well known of these reflections is Susan Sontag’s On Photography (1973), where she observed that images of violence not only “transfix”, they also “anesthetize”. Critique is blunted; compassion fatigue hits in. People get accustomed to barbarian ways. But other critics have pointed to the opposite effect: rather than viewers becoming blasé about bloodshed, such images may excite them. Artists and audiences alike could end up celebrating death and openly fetishizing courage, gallantry, and honour. Art can turn violence into a tempting melodrama or consumable drama; ‘war as hell’ is beguiling. Personally, I prefer the reflections of cultural critic Ariella Azoulay in The Civil Contract of Photography (2008). In that book, she argues that art can be a means through which citizenship can be assessed and political action conceptualised. Art is particularly powerful because of the way it disrupts the boundaries between witnesses and political actors. A photograph is a “civil contract” that binds together the photographer, photographed people, and spectators. It speaks not only to aesthetics but to power as well and, as such, is as imbued with ethics as any other cultural product. For Azoulay, creating and viewing war-art becomes a civic skill, making us less inhuman.

Do you have any art tips for participants entering our contest?

I wouldn’t dare advise artists! They hold worlds of creativity in their own hands – transfix us!

If you'd like to enter the Art of War contest, or wish to find out more about the forthcoming Art of War DLC, you can visit our page here for more information. The deadline for submissions is fast approaching (Wednesday, 15th July), so please make sure you enter in time. Good luck, artists!